Biography

A Man of Laws -- What is generally known about J.A.P. Campbell Sr.

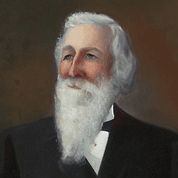

J.A.P. Campbell Sr. was a child prodigy who could read by the time he was four years old. He was born to a well-to-do family in South Carolina in 1830. After he moved to Mississippi with his family when he was 15, he rose quickly to political prominence in pre-Civil War Mississippi. By the time he was 35, he had become a well-known lawyer, congressman and then speaker of the Mississippi house of representatives, leader of Mississippi's secession from the Union, noted orator, Civil War Colonel, and military judge. After the Civil War, he became a Mississippi Circuit Court judge, then state Supreme Court Justice. For many of his 18 years on the Mississippi Supreme Court, he was the Chief Justice.

Campbell’s legal career brought him widespread admiration. He was called “the author of more legal reforms than any other lawyer, judge or legislator in the State1Citation: “Autobiography of Judge J.A.P. Campbell: Written for his Descendants on the 84th Anniversary of His Birth, March 2 A.D. 1914,” Daily Clarion Ledger, Jackson, Mississippi, October 22, 1914..” He has also been called “the father of white supremacy” because he was “the architect of the Mississippi Plan which established legal and official White Supremacy in the South2Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 1..” The Mississippi Plan became a blueprint for the rest of the U.S. South to prevent Black equality with whites.

Through his career, he delivered numerous speeches, published several letters, and wrote judicial codes that called for the maintenance and/or restoration of white political rule in Mississippi. In 1875, he served along with “General” James Zachariah George as part of the Democratic state committee that overturned Black legislative gains in Mississippi. The goal was to restore a white majority in the legislature (which still exists in 2022). Campbell called this a “glorious campaign3Citation: “Autobiography of Judge J.A.P. Campbell: Written for his Descendants on the 84th Anniversary of His Birth, March 2 A.D. 1914,” Daily Clarion Ledger, Jackson, Mississippi, October 22, 1914..” His Mississippi code of laws, which was adopted in 1880, still serves as the backbone of laws in Mississippi today.

He publicly bemoaned post-Civil War political gains made by Blacks. In a letter to the editor of the Daily Clarion-Ledger, published June 13, 1890, he wrote that “the negro hordes enfranchised among us [are] without fitness to participate in governing4Citation: “Plural Suffrage Plan,” Clarion Ledger, June 13, 1890, p 1..” He called for Mississippi to “[f]ree the negro from all concern about politics, for which he is totally unfit, and let his attention be turned to pursuits for which he is suited, and he will be both happy and useful5Citation: “Plural Suffrage Plan,” Clarion Ledger, June 13, 1890, p 1..” He called out “the evil [of] a large negro majority” in his letter to the editor of the Mississippian published June 25, 1890.

In 1892, Campbell said in a speech: “. . . I declare my belief unshaken as to the justice and righteousness of our Confederate cause [which] . . . drew together in harmonious action the members of the superior race, with the inevitable result that the inferior went down politically before the united action of the whites. The brief and disgraceful reign of inferiority and ignorance has passed away forever, let us hope, and the superior race again controls the entire South6Citation: Josiah A.P. Campbell, “Oration at the Third Annual Reunion Grand Camp Confederate Veterans, Jackson Mississippi, July 12, 1892.” Pamphlet in Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson Mississippi..”

When he died in 1917, he was the last living signer of the Confederate Constitution. Before he was buried, his body laid in state in the rotunda of the Mississippi capitol, where hundreds of mourners filed past. His funeral was “one of the largest ever seen in this city7Citation: Jackson Daily News, Friday January 12, 1917. Page 2..” Numerous published eulogies and later biographical profiles lauded his leadership and enormous impact on the state.

He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Jackson, Mississippi.

The Man Behind the Laws -- What is less known about J.A.P. Campbell Sr.

Much of what is publicly known about the personal life of J.A.P. Campbell Sr. is from the published writing and public remarks of iconic Black activist James Meredith. Meredith was the first Black to attend the University of Mississippi, gaining admission in 1962 amid National Guard troops sent by President John F. Kennedy.

J.A.P. Campbell Sr. fathered at least one child with a woman named Millie Brown. First classified as white, and later as Black, she is believed to have been born around 1844. Their daughter, Francis/es Brown, was born between 1862 and 1865 in Attala County Mississippi. She was James Meredith’s grandmother.

Campbell’s public stance on white supremacy masked his personal relationship with his Black descendants. In his article, “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith wrote about his great grandfather J.A.P. Campbell:

“J.A.P. Campbell . . . became displeased with the results of White Supremacy and spent the last twenty-seven years of his life teaching his own Black bloodline how to dismantle White Supremacy. For this, he has been written out of the history of Mississippi and the South.

. . . during the final years of his life he devoted most of his time to establishing educational programs for the Black Race, as well as, teaching them about the importance of land ownership and other economic developments. He also decided to acknowledge and to teach and to guide his own Black blood relatives8Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 1-2..”

Campbell’s own words provide some support for Meredith’s writing. It was 1890 when, as the then Chief Justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court, Campbell published two letters to the editor of the Clarion-Ledger, arguing that Blacks should not be disenfranchised from having the vote. Although he clearly articulated his white supremacist views (cited earlier in this biography), Campbell’s tolerant views about Black enfranchisement were extremely unpopular with the hard liners at the Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890. They rejected Campbell’s contention that whites would not be harmed if Blacks maintained their access to the ballot box. The 1890 Mississippi constitution was then written to include “new provisions for poll taxes, literacy tests, residency requirements and other devices that effectively disenfranchised nearly all blacks . . .9Citation: Wikipedia entry “Redeemers,” accessed June 9 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redeemers”

Campbell remained Chief Justice for four more years, after his 1890 views were rejected. He retired in 1894 at the age of 64. Meredith wrote:

“I know from conversations with my father Cap Meredith, who was the grandson of Judge Campbell, that the real reason for his leaving the service of Mississippi government was his deep disappointment with the corruption and extra-legal manner in which the affairs of state were being conducted after the adoption of the White Supremacy Constitution of 189010Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 39.”

. . .

“J.A.P. Campbell was too much of a man of family to do anything other than remain true to his vows of marriage. However, of greater importance to my own reality, he decided to meet his responsibility to his other bloodline, although legally and officially, he could not recognize it as part of his family because of the very laws that he had caused to be the law of the land in Mississippi. Nevertheless, my Great Grandfather decided to teach my father, his Grandson, Cap Meredith, everything that he knew11Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 82.”

. . .

“Judge Campbell, who was always treated with the greatest of respect in Attala county by all, introduced Cap to every man of importance in Attala county and made sure that they knew what relationship Cap was to him and privately got every white man of significance in Attala county to pledge to always remember and respect these facts12Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 85.”

. . .

“Judge Campbell always told my father that his greatest disappointment was over the dehumanizing of the Black Race after taking back political power after the Reconstruction era. His goal was to establish political dominance in the white race. He never intended to return the Black Race to a condition of servitude as had become the reality by the end of the Nineteenth century in Mississippi. His plan was to leave the Black Race with the franchise granted by the Reconstruction laws and increase the voting power of the white race to the extent that would guarantee their control of state government.

He wanted to make the Black Race a class of small farmers who owned their own homes and farms and took care of their own local affairs, including the education of their own children. One of his primary reasons for quitting the Supreme Court was to use his time to make Attala county a model of what he thought the new reality for the Black Race should be13Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 86.”

. . .

“Attala county is the only county in the State of Mississippi that has no record or account of any Black person ever being lynched in the county, from the Civil War in 1865 to the present. This is absolutely the result of the work of my Great Grandfather, Judge J.A.P. Campbell. . . . He took an active interest behind the scenes in the establishment of a good education system for the Black Race in Attala county. The result is that today the highest percentage of Black college graduates in any county in the entire United States are in Attala county, Mississippi. . . . Judge Campbell went on a mission to help Black families in Attala county to buy land and as a result, the largest number of Black land owners in America at the beginning of World War Two were found in Attala county Mississippi. . . . My Great Grandfather was most anxious to see that the Black Race in Attala county was fairly included in the labor pools of the new industries that were rapidly being developed in Attala county since the completion of the railroad link. He urged all employers to hire local Blacks in their labor force rather than recruit poor whites from other areas. He was very successful in this effort between the time of his retirement in 1894 and his death in 191714Citation: “The Father of White Supremacy,” James Meredith, 1995, p 87-88..”

The fact that J.A.P. Campbell Sr. had Black children and grandchildren was not unique in the pre- and post-Civil War South. Parallels in other slaveholding families have been documented in genetic research and family genealogies numerous times15Citation: Parra, Esteban J.; Marcini, Amy; Akey, Joshua; Martinson, Jeremy; Batzer, Mark A.; Cooper, Richard; Forrester, Terrence; Allison, David B.; Deka, Ranjan; Ferrell, Robert E.; Shriver, Mark D. (December 1998). "Estimating African American Admixture Proportions by Use of Population-Specific Alleles". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1839–1851. doi:10.1086/302148. PMC 1377655. PMID 9837836.. This situation was so common that the term “children of the plantation” was used during slavery times16Citation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Children_of_the_plantation, accessed June 11, 2022.. “Politicians, judges, ministers, doctors, and planters with several holdings and elaborate business connections had vast spaces, often connected by poor roads, to cover. Their wives had to understand17Citation: Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, 1988, UNC Press, page 12..” J.A.P. Campbell’s prominence in state and regional politics certainly mirrors this situation18Citation: Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, 1988, UNC Press, page 26. And his views on white supremacy also paralleled those of his time and culture in Mississippi.

A white supremacist’s overt advocacy for his Black descendants, or any Blacks, however, was not a cultural norm in J.A.P. Campbell’s lifetime. J.A.P. Campbell, the man behind the laws, whose legal career helped build the framework for a nationwide system of white domination, tried to redirect the extremist white supremacists of his time toward a more generous co-existence with Blacks.

Although he failed in this effort, a fuller exploration of J.A.P. Campbell, a man of laws and the man behind the laws, can bring a deeper understanding of how one’s personal circumstances can change one’s perception of what’s right and wrong.